Nation

S/East’s killings: How Buhari’s gambit created chaos in the zone

Rated the most secure geopolitical zone in Nigeria by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) in 2016, the South East has, over the past few years, witnessed a level of violence not seen since the end of the civil war in 1970.

What was once Nigeria’s safest region has become a theatre of bloodshed, forced disappearances, and systemic state and non-state violence, an outcome Amnesty International and analysts trace partly to the heavy-handed response of former President Muhammadu Buhari to pro-Biafra agitations.

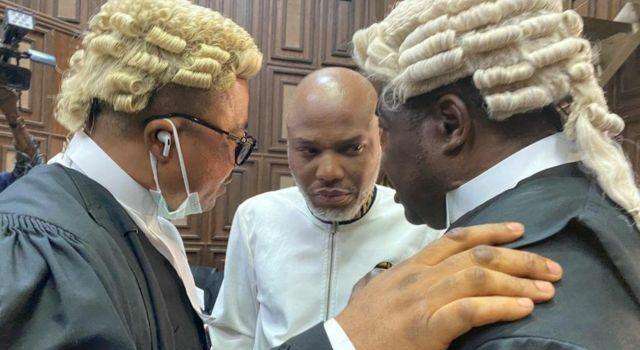

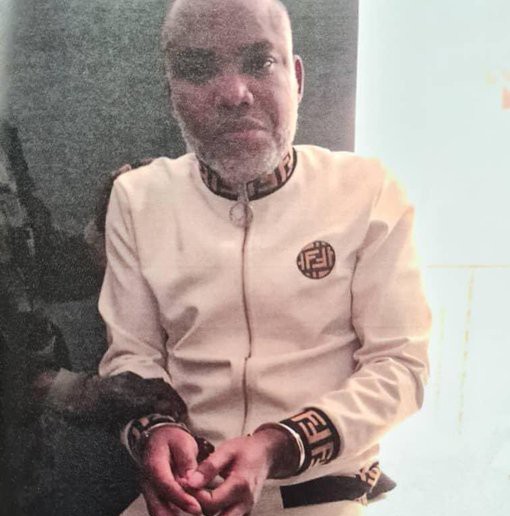

The Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB), led by Nnamdi Kanu, had intensified calls for a separate state of Biafra in 2012, deploying Radio Biafra as its main propaganda tool. Initially, the movement attracted little attention outside Igbo heartlands.

That changed dramatically in October 2015, when Kanu was arrested shortly after Buhari took office. The arrest ignited mass protests across Onitsha, Aba, and Owerri. Young men, draped in Biafran flags, poured into the streets, chanting solidarity songs.

Rather than dialogue, the state responded with bullets. Human rights groups documented multiple cases of security forces firing live ammunition at unarmed demonstrators. “That brutal crackdown set the tone,” says then Enugu-based lawyer and rights activist, Chidi Anthony. “It convinced a generation that the Nigerian state sees them as enemies.”

Violence Begets Violence

When Kanu was eventually granted bail in April 2017, his stature had grown astronomically. IPOB rallies attracted thousands, prompting Buhari to launch Operation Python Dance, a military exercise that resulted in scores of civilian deaths. Soldiers stormed Kanu’s Afara-Ukwu home in September 2017, forcing him to flee. By the time his images surfaced from Israel in late 2018, the South East was already a cauldron of fear.

The situation deteriorated further in December 2020, when IPOB floated the Eastern Security Network (ESN), ostensibly to repel marauding herdsmen. It quickly became a flashpoint for clashes with security forces. In June 2021, Kanu was extraordinarily renditioned from Kenya, rekindling unrest. IPOB announced a Monday sit-at-home protest to demand his release, a decision it later revoked. But by then, a breakaway faction led by Finland-based Simon Ekpa had weaponized the directive, enforcing it with terror.

Markets shut, schools closed, and highways became death traps. Amnesty International estimates that between January 2021 and June 2023 alone, at least 1,844 people were killed across the five South East states. “The Nigerian authorities’ persistent failure to address the security crisis has created a free-for-all reign of impunity,” Amnesty declared in its August 13, 2025 report titled, A Decade of Impunity.

A climate of blood and fear

The report chronicles atrocities committed by state forces, IPOB-linked militias, and a motley of actors, from “unknown gunmen” to cult gangs, and the state-backed Ebube Agu paramilitary outfit. In Imo State alone, gunmen killed over 400 people between 2019 and 2021, torching police stations and homes. Amnesty investigators interviewed more than 100 witnesses, uncovering chilling tales of arbitrary arrests, torture, and enforced disappearances.

One of the most haunting cases is that of Sunday and Calista Ifedi, a couple seized from their Ezeagu home in Enugu State by Department of State Services (DSS) operatives on November 23, 2021. Four years on, they remain missing. Their 21-year-old daughter told Amnesty:

“Since my parents’ abduction, things have been exceedingly difficult. I dropped out of school to take care of my siblings. I suddenly became both a mother and father.”

This story mirrors dozens of others: Ikechukwu Henry, a young caterer from Orlu, Imo State, dragged out of his home at 2:00am by men in military uniform in August 2021. His wife recalled to Amnesty:

“They beat my husband so badly… When I visited the army division, they told me he had been moved to Abuja. Since then, nothing.”

Similarly, Eberechi Ukaegbu, 50, was abducted from his home in Obingwa, Abia State, in March 2021. Despite frantic searches at police and DSS offices, his family has no trace of him. “His wife and five children are devastated,” Amnesty notes.

Such cases are not isolated. They form a grim pattern. Security forces deny holding these individuals, leaving families trapped in anguish. “No one knows exactly the number of people killed or missing since 2015,” Amnesty warns.

Buhari’s covert war?

Critics argue this spiral of violence was not accidental, but the outcome of a deliberate policy. “This report is absolutely correct,” insists Bob Okey Okoroji, a lawyer from Imo State. “I lost six direct cousins – three killed by security forces and unknown gunmen, three disappeared. They were murdered in their homes, not in any camp.”

Okoroji accused the Buhari administration of masterminding covert operations: “It was carefully crafted and fully funded by Buhari’s government. Initially meant to degrade IPOB, it later expanded to eliminating Igbo youths of military age.”

He alleges a nexus of political betrayal and profiteering: “Heads of security agencies became stupendously rich. Buhari used mercenaries like Asari for cover missions. Some Igbo politicians collaborated, seeing it as their ladder to power.”

This claim aligns with long-standing suspicions among residents that the crisis has been fuelled by vested interests exploiting chaos for political or financial gain.

Amnesty’s findings lend credence, highlighting Ebube Agu, a security outfit created by South East governors in April 2021, as a notorious tool of repression. The militia, the report states, carried out “arbitrary arrests, torture, extrajudicial executions, and destruction of homes.”

A zone turned into killing fields

Once bustling communities have become ungoverned spaces. Amnesty cites Agwa and Izombe in Imo, and Lilu in Anambra, where gunmen displaced residents, and dethroned traditional rulers. Parts of Orsu, Ikigwe, Arondizuogu in Imo, and Ihiala in Anambra, are currently hotspots, terrorized by a gang of gunmen allegedly led by a certain Gentle De Yahoo.

The fear is palpable. Weddings and burials, once sacrosanct communal rites, are relocated to distant cities. “I haven’t slept in my Orlu home for four years,” Okoroji laments. Roads that once thrived with festive traffic now wear the look of ghost towns on Mondays. Traders risk death for opening their shops. Teachers are flogged for showing up in class.

Videos reviewed by Amnesty show men whipping schoolchildren for defying sit-at-home orders. In one chilling incident, gunmen stormed Ishieke Market in Ebonyi on July 4, 2023, firing sporadically, torching goods, and killing commercial motorcyclists.

The region’s economy lies prostrate. Billions of naira in productivity have been lost to forced shutdowns. Yet, beyond the economic toll, the human cost is staggering—thousands dead, countless missing, families shattered, and an entire generation traumatized.

A report in May by SBM Intelligence revealed that Southeast has lost an estimated N7.6 trillion in four years on account of sit-at-home enforcement.

Amnesty International’s latest investigation paints a chilling picture of what life has become in the region. Between January 2021 and December 2024, the organisation documented at least 1,000 extrajudicial executions and unlawful killings, along with the enforced disappearance of more than 800 people suspected of supporting, or sympathizing with separatists.

Most of those who vanished were young men, breadwinners, artisans, students, plucked from their homes or street corners by heavily armed operatives, never to be seen again.

“Security forces have turned the South-East into a graveyard of human rights,” said Isa Sanusi, Amnesty’s Nigeria Director. “People are being abducted in broad daylight, detained in secret facilities, tortured, and in many cases killed – all outside the boundaries of law.”

For families of the missing, hope is a cruel tormentor. They shuffle from one police station to another, clutching photographs and prayers, pleading for answers that never come.

Amnesty recounts the story of Obinna (surname withheld), a 27-year-old trader from Imo State, who disappeared in June 2023 after soldiers stormed a market in Orlu. His mother told investigators: “They came in armoured trucks, shooting. Obinna was dragged into one of the vehicles. I have been to every station; nobody will tell me where my son is. I don’t even know if he is alive.”

Such testimonies echo across the region, underscoring a systemic pattern of enforced disappearances that Amnesty says amounts to crimes under international law. In many cases, relatives who dare to ask too many questions face harassment or extortion by security operatives demanding bribes to “search” for loved ones. Some families have reportedly paid millions of naira, only to be met with silence.

Neither the Nigerian Army nor the police have admitted responsibility for the disappearances, and no security operative has been prosecuted for these crimes. Instead, official statements often frame the victims as “terrorists,” or “unknown gunmen,” language that erases their humanity and pre-judges their guilt, the report said.

Sanusi warns that this culture of denial emboldens perpetrators. “When the state treats accountability as optional, abuses become policy,” he said. “The families of the disappeared deserve justice, and the government must break the wall of silence.”

Calls for Investigation

The shadow of fear dictates daily life in parts of the South-East. Nightfall brings anxiety, with residents avoiding gatherings or late travel lest they be swept up in a raid. Checkpoints dot the highways, manned by jittery soldiers whose triggers seem lighter than their discipline. Amnesty’s report details instances where civilians were shot dead for refusing to pay bribes or for failing to stop quickly at roadblocks.

One particularly harrowing episode occurred in August 2024 in Ebonyi State, where security forces reportedly executed nine young men accused of being members of the ESN. Witnesses told Amnesty that the men were arrested alive during a raid, only for their bullet-ridden bodies to surface days later. No investigation was launched.

Amnesty is calling for an independent judicial inquiry into the killings and disappearances, and for all security units implicated in abuses to be withdrawn from the region. It also demands that secret detention facilities be shut down and that families be told the fate of their loved ones.

For now, the South-East remains trapped in a grim paradox: a region yearning for peace, yet crushed between the iron fist of the state and the menace of armed separatists. And as the cries of grieving mothers fade into the silence of official indifference, one truth stands stark: in Nigeria’s war without end, it is the innocent who bear the heaviest burden.