Business

Investors take stock as equities plummet

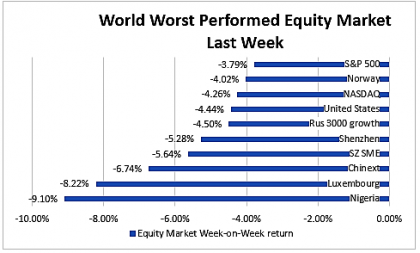

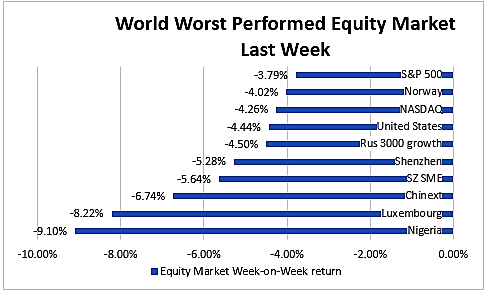

To be sure, 2018 has proved to be a harsh year for local investors in Nigeria as the stock market tumbles to its lowest value in ten years. The Nigerian All Shares Index (ASI), a measure of the aggregate performance of the local stock market, has dipped by a worrisome 8.99 per cent on a year-on-year basis and 16.37 per cent year-to-date. ”If you had any illusions about stingy returns in the market in the year” says FSS Securities, managing director, Chris Okenwa, ”welcome to your greatest nightmare”.

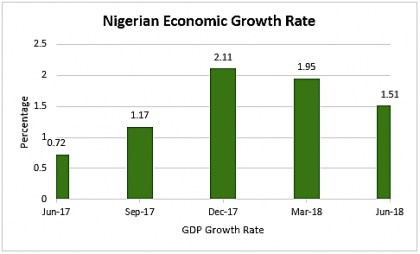

Indeed the market has swung along a decline path in the last three months as foreign investors (who are responsible for about 60 per cent of market activity) have made a dash for the door as they sell off heavy loads of shares to improve yearend liquidity and hedge against growing uncertainty in the country’s political environment. With 2019 general elections prepped for February and the current administration becoming increasingly unpopular as a result of slow economic growth (the country’s GDP is anywhere between 1.5 and 1.7 per cent) and staggering unemployment (estimated by the national statistics bureau (NBS) at 18.8 per cent as at December 2017), the outlook for the nation’s political transition and economic stability appear grim.

”the economy is certainly going to be a big factor in the run up to next year’s elections” says Suraj Akinyemi, an economist, ”the populace is clearly tired of the many excuses made by the administration for lack of economic development, high domestic interest rates, falling manufacturing output and rising fiscal deficits; factors which have conspired to make the government look profligate and inept.” The government’s persistent calls for support of its anti-corruption crusade has worn thin as its welfarist cash transfer and school feeding programmes burn holes into the sides of the treasury’s vault turning a 2015-political mania for change into a 2019 battle cry for structural reforms and regional fiscal independence.

”the economy is certainly going to be a big factor in the run up to next year’s elections” says Suraj Akinyemi, an economist, ”the populace is clearly tired of the many excuses made by the administration for lack of economic development, high domestic interest rates, falling manufacturing output and rising fiscal deficits; factors which have conspired to make the government look profligate and inept.” The government’s persistent calls for support of its anti-corruption crusade has worn thin as its welfarist cash transfer and school feeding programmes burn holes into the sides of the treasury’s vault turning a 2015-political mania for change into a 2019 battle cry for structural reforms and regional fiscal independence.

The conflict between welfarist doves and fiscal hawks is gradually shaping the new narrative on fiscal policy management in the country as it opens up fresh discussions on what is required to pull the Nigerian economy out of the rut. While welfarists economists (who presently dominate the administration)insist that government as constituted is the best agent to push the cause of national growth forward, their counterparts on the conservative frontline insist that what the economy actually requires at the moment is for government to keep its fingers off the levers of growth and allow private initiative to drive development. This school of thought argues that the government must stay clear of spiraling public debt (debt service as a proportion of revenue is above 60 per cent for 2018)and refrain from profligate public spending (budget deficit is about N1.3 trillion and counting) by way of cash transfer programmes that add little or nothing to productivity and output.

The inflation deep dive

Tony Madojemu, a chartered accountant and director of one of the country’s newer generation commercial banks argues that, ”the government needs to be circumspect. A large fiscal deficit creates little room for private sector growth and development as the government has consistently funded its bad book balances through the sale of treasury bills there by cutting out credit to private enterprises.” According to Madojemu,”this seems to have pumped up commercial lending rates and pushed manufacturers and traders to feed from the bottom of the lending pot like mosquitoes”, he says. Indeed 30-day treasuries have recently traded between 12 and 13 per cent per annum, or what comes to slightly higher than October 2018 domestic inflation rate of 11.26 per cent.

Analysts note that positive risk free rates of 74 to 174 basis points should (at least in theory), encourage savings and lead to the withdrawal of money from circulation, which in turn should result in a fall in inflation rate.So has this happened? Yes, it has.

Domestic inflation rate has slumped from a towering 18 per cent in February 2017 to a more benign 11.26 per cent which in itself was a marginal dip of 2 basis points from the earlier 11.28 per cent in September 2018.Lower inflation rates over the last twenty months should normally be followed by falling interest rates and an expansion in domestic credit, this has not happened so far. The trouble appears to be that the central bank of Nigeria, the country’s chief banking regulator and monetary policy monitor, has continued to keep interest rates high to discourage consumption spending and reduce potential demand pressure on the foreign exchange market. The strategy has worked well by canning inflation rate at below 12 per cent per annum and stabilizing the Naira to dollar exchange rate at about N360/$ in the unofficial market while fixing the official market rate at N306/$. ”This has given a notional sense of comfort”, says Madojemu, ”but has hidden the rising wave of concern over unemployment, social security, and crumbling industrial output”.

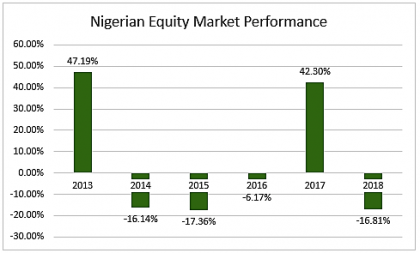

The stock market has reflected these nuanced perspectives of growth as longer term views of market declines or bearishness has been spray-painted with short but negligible bullish bursts. The ASI has dropped well below last year’s strong upward path (the market closed at a sturdy yield of over 40 per cent on a year-on-year basis in 2017) and reflects a considerably mooted enthusiasm about growth in the coming year, 2019. Not even the expected large public sector election spending has succeeded in lifting the dark mood of investors as foreign portfolio managers opt to short the market in large recent equity sell offs.

The downward market trend is expected to continue right into the first quarter of the year and right after the elections. The second quarter may see the market rebound mildly depending on election results. If the current administration stays in office the market will stay flat as investors would expect no major change in policy and therefore no major improvement in the country’s growth outlook.

The Central Bank of Nigeria’s monetary policy inertia as captured by its recent Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) decision to keep Policy Rate (MPR) at 14 per cent, Liquidity Ratio at 30 per cent and Cash Reserve Ratio at 22.5 per cent supports investors pessimism for an early growth recovery. The CBN has held policy rates at the same level for 23 months suggesting that the regulator is all too happy to leave well alone as long as inflation remains in the lower double digit and foreign exchange rate stays relatively stable.

According to Dr Kemi Akeju, a lecturer at the Ekiti State University, ” monetary policy hawks at the bank are unlikely to shift grounds any time soon. Relatively low inflation rate and stable foreign exchange numbers are too sweet an economic incentive to give up. A local adage says if you are going to eat a frog, eat a big fat juicy one or else perish the idea. The CBN has no motivation to change tack”, she notes.

But that could prove economically expensive in the morning after the 2019 elections as slumping international oil prices and declining government revenues could widen the fiscal deficit further thereby raising domestic interest rates and worsening the jobless rate. Notes Akeju, one of the country’s few specialists in economic demography, ”the economists lag is almost always the politicians nightmare”. In other words the consequence of tight monetary policy usually takes some time to manifest and even when it does the full impact may only reveal itself several months down the road.

So far the CBN seems to have assumed that its policies have had only short term immediate impact on the economy and that the longer term consequences of its policies are of minor importance. Unfortunately this is not exactly true. To be sure, tight money supply has raised short term interest rates and snuffed out local private credit, but the consequence of falling production and lower domestic consumption could take much longer to appreciate.

A Cashless Christmas

In the meantime the capital market is likely to respond to a regime of loose fiscal and tight monetary policy by money managers taking a swing at alternative markets, indeed with foreign portfolio (equity) investors taking a negative or bearish long term view of the capital market as slower growth and skinnier profits lead to lower earnings per share and slimmer dividend payouts(a combination of factors that could pull share prices lower and cut down prices of government Treasuries), the outlook for the local capital market in the near term is dim. Christmas this year may come all too soon for those that find their investment portfolios light, their pockets leaky and their hopes of a repeat 2017 market return dashed.